.jpg)

Mycelium fascinates through its ability to colonize substrates—including straw, sawdust, husks, or fibers—and bind them from within to form a coherent biocomposite structure. In this sense, it generates a new material by bonding natural elements together during growth.

Many low-impact materials originate from organic waste, but their transformation typically relies on industrial steps such as cutting, adhesives, and the use of thermal or mechanical energy to achieve a defined shape. Mycelium follows a different logic. It transforms loose particles into a coherent body with minimal intervention and very low embodied energy, guided by molds, controlled humidity, and time. Form emerges through a biological process rather than energy-intensive manufacturing, resulting in fewer production stages, less waste, and components that are close to their final geometry.

This does not mean mycelium is inherently “more sustainable” than other mature bio-based materials. Its novelty lies elsewhere: in relocating manufacturing to growth. Human labor defines the conditions, while form and cohesion emerge biologically, reducing the need for machinery and subsequent industrial operations.

For years, we've seen mycelium used as an experimental material in installations, academic research settings, and temporary pavilions. Today, with architects and engineers working under increasingly stringent carbon constraints and limited budgets, the question has expanded from experimentation to understanding how and where mycelium can operate as a viable technical option within specific architectural systems.

The strength of mycelium-based materials is closely tied to how they are produced. Their lightness, open porosity, and low intrinsic toxicity make them well suited to interior environments, where materials are in direct contact with occupants. Because they do not rely on resins or complex synthetic additives, they emit fewer chemical compounds indoors. From a performance perspective, their porous structure supports acoustic comfort and passive humidity regulation, while the absence of added VOCs contributes to better indoor air quality. Today, their main contribution lies not in load-bearing functions—at least not yet—but in non-structural applications where environmental, health, and functional performance is direct and verifiable.

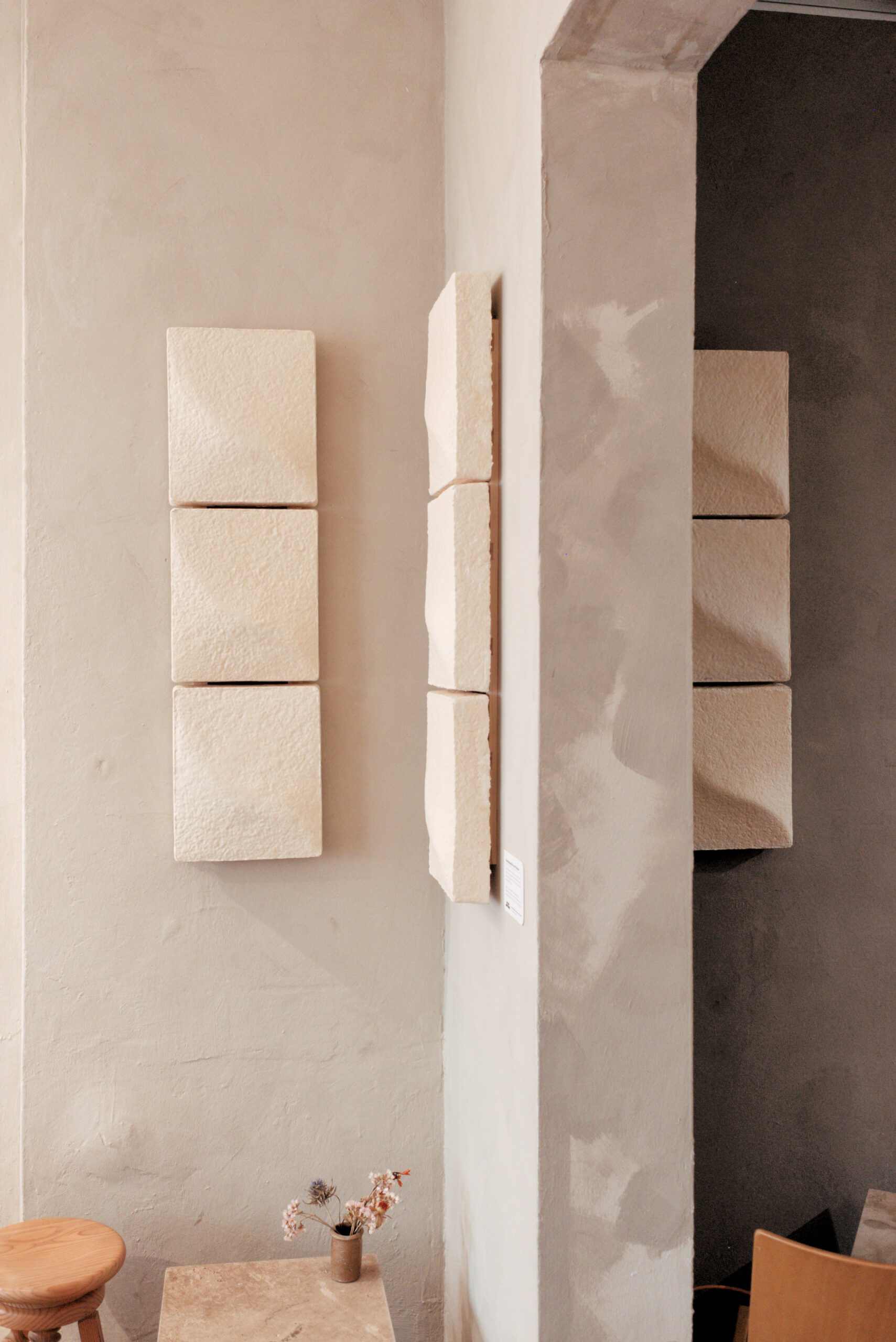

In practice, mycelium-based materials can already be specified across a range of interior functions. Mycopanel by Myconom Bio Materials offers mycelium wall panels made from agricultural and textile waste, providing VOC-free sound absorption with a low carbon footprint. MycoLutions Acoustic Panels deliver environmentally friendly acoustic solutions for interior spaces, combining high sound absorption with circularity and compostability.

In more technically defined applications, several products have passed standardized fire reaction and low-emissions tests, positioning them as credible alternatives to conventional interior materials. This includes insulation systems such as Mykor’s MykoFoam—a breathable, fire-resistant thermal and acoustic insulator—and Mogu’s interior panels and flooring, now used in offices, retail spaces, and cultural buildings across Europe.

Beyond cladding and insulation, mycelium is already present in hybrid applications where growth and appearance become part of the architectural expression—from wood-like boards such as Comu Labs’ MycoWood to biocomposite panels by MIMBIOSIS, where material origin and texture remain visible. The same logic finds its way into exterior applications, such as VisiPaver by Visibuilt, a paving system grown from agricultural waste and mineral aggregates, where mycelium acts as a biological binder and leaves a warm, legible surface pattern shaped during growth.

In a context of regulatory pressure and constrained budgets, the materials gaining traction are those that reduce friction: fewer production stages, fewer toxic inputs, less waste, and clear, reliable technical performance that streamlines specification and compliance.

Here lies the value of mycelium: the ability to self-generate with limited processing and stabilize into specific components that deliver tangible, essential benefits for architecture. Framed this way, mycelium is not an experiment sustained by narrative appeal, but a concrete technical option whose low-carbon footprint is intrinsic to its growth—and whose long-term relevance depends on how performance insights are captured, compared, and shared across design teams over time.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)